This article was first published in ‘White Print’ – a braille magazine for the visually impaired, founded and published by Upasana Makati.

On your journey of life, you meet people who become a part of you and the family you were born with grows larger and stronger. I had the good fortune of being introduced to the work of two people who have the largest hearts. For them – the people of the country form the rest of their family.

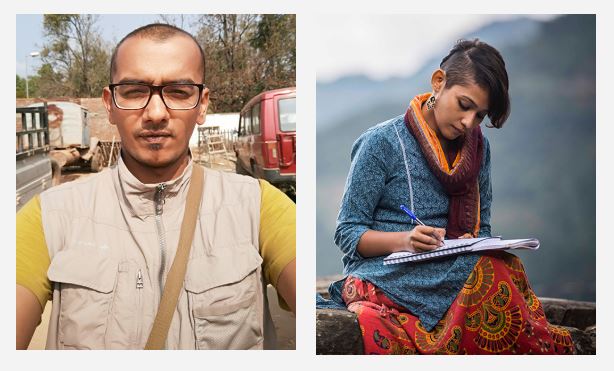

Meet Piyush and Akshatha founders of ‘Rest of my Family’ – a travel based social work-through-art initiative that spreads the message of empathy, kindness, compassion and inclusion.

In their words,

“Rest Of My Family is not just a project or an organization. It is an attitude, an emotion, an inclusive world view that if adopted can create a more kind and caring world.”

“All of us, where ever we are, whatever line of work we are in, whatever be our capacities, can work towards making this world a little less indifferent by looking around ourselves and accepting everyone around us as our own and supporting those who might need a helping hand; like we would do for our dear loved ones.

Just the simple realization that everybody is our own and their well being is our responsibility has empowered us so much that just the two of us (with help from so many other people) have managed to do everything that we already have and all that we continue to strive to achieve. Similarly, we believe, understanding the self and its role in the collective, in this light can empower each one of us to give back to the society, be more compassionate and achieve amazing things. Not as a burden, compulsion or charity or favor. But with acceptance of the fact that all of us are in it together. That we are all on the same side”.

Piyush and Akshatha share insights into their beautiful journey with the Rest of My Family.

Give us a background about your work lives before Rest of My Family and the new journey you embarked on from 2013.

We are both qualified engineers from the National Institute of Technology Karnataka. After working in the corporate world for about two years, we realized that it was not the direction we wanted our lives to go forward in. The seed for Rest Of My Family was sown in 2010 when we decided to take up socially relevant work and dedicate our lives to art and philosophy and find ways to bring both these disciplines together.

Between 2010 and 2013 while nourishing our initial thought, I worked on various independent photography projects; fiction and non-fiction films while Akshatha explored her tryst with journalism.

It was during this period that both of us began traveling to rural and tribal communities as frequently as our resources allowed us to do so. We also shared our findings through photo-stories. We did this for a while and initially thought that writing about social-issues would positively impact the lives of the ignored sections of the rural and tribal communities and would draw the attention of those who have the necessary resources.

However, with time we were convinced that writing/documenting alone seldom results in a constructive impact on the individuals and communities that are being written about. We knew that there was a lot more that needed to be done.

As we travelled and lived with far-flung families and communities, we were given so much love, care, protection from people who were strangers to us at that point. This made us strongly believe in the fact that all social, cultural walls and structures separate man from another man, one family from another family, and one culture from another culture.

The more we travelled and the more we met new people, our social walls melted away. Over time, fear and suspicion was replaced with love and trust as a predisposition. We realized that everyone we met and lived with was a part of our own family. And, when someone is part of your family, just writing about their challenges and needs isn’t doing enough. Their problems are not just their problems alone, they become your problems too and you have to try your best to find a solution to these challenges with all our resources, ideas and limitations.

Rest Of My Family in its current form evolved overtime. By placing ourselves in the realm of uncertainty by way of being on the road and living with communities that were unknown to us, we had no choice but to place our faith in humanity.

In 2013, we gave up our home, our belongings and everything else we owned to live a life on the road and dedicate ourselves to a single idea and cause which is the philosophy of Rest Of My Family. —

On 3rd February 2016, we embarked on a nonstop one-year drive through rural and tribal India. Our journey was made possible because of a successful crowd-funding campaign. Since then, as a part of Rest Of My Family, we have documented and lived with numerous rural and tribal communities all across the country (Karnataka, Maharashtra, Chattisgarh, Orissa, West Bengal, Assam).

Throughout the drive, we documented various communities and issues across six states: farmer issues in drought-hit regions of Karnataka and Maharashtra, the current situation of Devadasis in Koppal (Karnataka), social issues faced by the Lambani community in Chincholi (Karnataka), the situation of adivasis and the Naxal-state conflict in Bastar, Chattisgarh, issues faced by Bonda tribe in Orissa, Human trafficking and other challenges near India-Bangladesh border in West Bengal and the current situation of The Biate Community in Assam.

In the last three years, we have been able to:

- Sponsor education for over 400 underprivileged children across six states

- Enable a cut-off (remote) community in Dhanushkodi with a community bus

- Initiate rural healthcare program in Bastar, Chhattisgarh. We are conducting two medical camps every month since July 2017.

- One bio-gas project in Bonda Hills, Odisha. We introduced biogas to the Bonda tribe in the region.

- Drinking water access project in Arsenic contaminated areas of North 24 Parganas district in West Bengal. Providing 16,000 liters of safe drinking water everyday.

- Formed Kharthong Organic Farmers Producer Company (KOFPO) in Dima Hasao, Assam. It provides better rates directly to the farmers.

- Provided a community bus to the fishermen settlement residing in Dhanushkodi, Tamil Nadu.

You meet and interact with so many people from the village on a daily basis. Tell us a few lessons you’ve learnt, someone who touched your heart and said something that has stayed with you since then.

We have been on the road for more than six years now and have met so many people from various communities and regions. On the surface, these individuals from varied backgrounds and regions seem so different from one another. The way they look, the way they speak, the way they dress, their history and so on. However, deep within there is nothing but similarity; a similarity that dwarves our differences. From Tamilnadu to Ladakh, from Rajasthan to Northeast, we have celebrated and cherished the cultural, linguistic and regional diversity and at the same time learnt so much about these similarities, about what connects us all.

It is in these underlying similarities that we hope to find unified solutions to myriad problems that plague individuals across the spectrum and seem so complex on the surface.

People in Nagaland might feel that the people there are the worst and their problems are unique, people at the other end in Rajasthan might feel that they are suffering the worst and so on. But, by cutting across various spectrums, eco-systems, regions we have understood that these notions are not entirely true. All communities, all regions are just subjectively experiencing manifestation of same human tendencies, social norms, preconceived notions and social values that have to been held to be harmless, non-violent, and peaceful. We just need to understand the flip side of some of these notions that might seem to work for us on front, but also end up creating the social evils we see around us.

For instance:

One social conditioning that enables most of us to unknowingly contribute towards all the indifference in the world (some more than others) and that enables a corrupt politician to be corrupt, a greedy middleman to be insensitive to the plight of farmers, a mining company CEO to be indifferent to the well-being of tribals is the unquestioned norm of being concerned with the wellbeing of a few loved ones and indifferent to the fate of all others.

None of them think that they are evil. Neither are they out there to deliberately destroy lives. They are just primarily absorbed by their own self-interest and are only focused on what they want out of that situation, i.e. a pie of public funds, vegetables at the cheapest rate, and tribal land for mining respectively.

Similarly, a film maker, media company, a news agency might go to a backward tribal community make a film that they want to, sell it, make money and move on. Leaving the community to their condition because even the film maker/media company, just like the middle man is only absorbed in what they need.

This is one reason why ROMF doesn’t stop at just documentation but also accepts the inherent responsibility in getting involved with community’s well-being.

In that sense, we believe, that our way of work is not just a working model that we have chosen, but the only responsible and inclusive way to work and be part of the society. We all need to get involved with people we interact and work with rather than treating them as means to get our work done.

When we are in the villages, our day usually revolves around the routine of the community as we go about understanding and documenting them. Handling community development projects in some of the most remote and disconnected places in the country can at times throw monumental challenges at us. When we first set foot in these areas, we spent a lot of time exploring the soul of these places and tribes, and understanding their plight on a fundamental level. We may not look the same. We may not speak the same language. But our hearts are all the same. It is this honest human connection that we have gained over the years of being on the road. And, that is perhaps our biggest achievement in life.

We are foremost interested in relationships and expanding our circle of belonging. Giving ourselves and the community time to understand and accept each other as our own. Everything else that follows is built on a trust, a sense of mutual welfare that we respect. So, all the communities that we work with don’t view us as ‘outsiders’ and we don’t view them as outsiders or ‘the others’. Hence, the community leaders, members are more than receptive, excited and supportive of everything we do with them.

Many people have touched our hearts and are special to us many in different ways. We have also found reflections of ourselves in many people from all over the country.

To name one – Lalpuia Ji and his family have given us a home to stay in the village in Assam where we live and work out of. We had been living and working there for months, when one evening he came up to us and said – “I didn’t know what the name of your project – Rest Of My Family means. So, today I asked my daughter Moi to explain it to me. She did and now I understand. I believe that I have also been a part of Rest of My Family’s journey. I always try to be there for others in their hour of need. My community, my fellow men and women. That way I am part of Rest Of My Family too”.

Lalpuia ji has contributed immensely to our work with the Biate Tribe. He is just like one of us and lives our philosophy in his own way and capacity, even before our paths met.

Has the ROMF journey changed you as people? Are you more grateful about life than you ever have been?

It has been an incredible journey so far. We haven’t had the time or space in the last few years to reflect upon it, but it has definitely changed us and continues to do so. We have found a way to others through ourselves and found ourselves through others. We have become more caring, loving, forgiving. Having said that, we aren’t perfect in any way. In fact it teaches us to work on our own shortcomings, and align ourselves with our vision.

Our circle of compassion and love is ever expanding. That has become our primary purpose in life – To expand our circle of compassion a little more everyday. We have forged strong bonds that will last several lifetimes.

We have our struggles too. Some days are hard, and in some moments we may find ourselves emotionally broken. But the joy that we feel every single day doing what we do truly makes us happy.

Today our life and work are one and the same. And knowing that we are doing exactly what our lives are meant for is priceless. It gives a sense of peace and satisfaction that no money can buy.

What is the most fulfilling aspect of undertaking these projects in the rural areas of the country?

As mentioned earlier our journey began as documentary people. Over time it just became clear that taking on the problems and challenges of the people who are our own, was our inherent responsibility. In that sense it is extremely satisfying to know that we are standing up to our responsibility no matter how monumental the challenges that lie ahead of us.

As Albert Schweitzer rightly said – “Life becomes harder for us when we live for others, but it also becomes richer and happier.”

That has been our experience as well.

We have met individuals who have waged battles against their own destiny to remain alive. We bid farewell to a few who succumbed to illnesses over a few months. We have met people who have carried the struggle and sorrow on their shoulders enough to destroy will and break faith in humanity. And yet, here they are thriving and surviving against all odds. We have met men who buried their children, mothers who shed tears for their slain sons, grandfathers who weep for their families that may not survive the year, daughters who stood up against atrocities. We have seen profound kindness in their souls as they accepted us – two strangers – into their lives and homes, and treated us as one of their own. It is only right for us to treat everybody as our own too.

A story that touched you the most.

There are many experiences that we cherish from our time with all the communities. It would be very difficult to pick one particular incident or experience that would stand out from the rest. Sharing a few of them here.

The first time we met Epa Lallura, he asked Piyush: “You came from lands unknown to us. We don’t speak the same language. We don’t look the same. And yet, when you called me epa (which means father. It is how we address elders in the community epa-father and enu-mother), I felt something. It meant something to me. Why is that?”

We didn’t know what to tell him. Over the two years, he often spoke about loss of Biate culture, language and music. He feared that the knowledge would perish with him. Some days, he chided us for not coming a decade sooner. He’d say, “You should have come when I was young. I would have been far more active than I am today.” A year later, we found our answer. It was the universe’s way of bringing us together so that the Biate music, culture, tradition and folklore remains immortal. Maybe that’s why we met.

The first time the elders gathered to sing songs of their past (this was back in 2017) and perform rituals that they no longer perform, Lalpuia’s mother played the gong at night and sang along with the rest. Lalpuia (whom we stay with in Thingdol) stood up and danced (their traditional dance) to the rhythm. He had tears in his eyes. Ever since the death of his little brother, many years ago his mother had stopped singing. That particular day, when the elders gathered on a moonlit night around the fire to rekindle their past, she sang again. “Enu never sang again after his death,” he said, “Today, she did after many years.” During Artist Connect again, the elderly women and men performed their traditional dances as well as sang songs of their past.

In Bodpada, one of the villages in Bonda Hills where we lived, when Piyush got Malaria, the grandmother living next door would come to our hut everyday with concern in her eyes. She would rub his feet with chuna and haldi since he had sprained his foot around the same time. Our assistant cameraman and I walked three kilometers from the dispensary to the village while Piyush was sent off on a bike with a person from the neighboring village. The next day, we walked three kilometers again to get the reports that indicated that he had tested positive for malaria. It was tough since the village has no bathrooms or toilets or plumbing and was situated in the forest. In conversation, when we asked the villagers if they suffered from Malaria this year, one of the men giggled and said to us, “Yes, I had it four times this year. It is pretty common in these areas.” Every household has lost at least one member to malaria in the village. The following year, one of the men whom we shared several cups of tea with almost every morning, died of tuberculosis. His wife is an alcoholic. They have a young boy.

In Davangere, we met a farmer whose wife committed suicide because the price of tomato reduced that year. There was no water left in the ground. His pump failed a week ago. Arecanut was barely fetching him any prices that year. Sometimes, the narrative of farmer crisis, farmer struggles and farmer deaths gets lost in mainstream media. For, that’s a story that has been told far too many times. But it has to be told over and over again. Their struggles and sorrows cannot be ignored.

In Thingdol, Assam, we met a young girl. Her name was Zir Sangpui. We saw her little feet scurrying along the paths of Thingdol throughout the day. Two-year-old Thlethle hung on her shoulder. She took care of her little siblings while her parents went to the fields every day. On some days, she would carry tiny logs of wood on her back and on a few days, she would carry pots of water.

One day, we asked her why she didn’t go to school and she said, “ My father does not have the money to pay for the fees,”. Her parents never went to school. They belonged to one of the poorest families in the village. Her father David had to make a tough choice between feeding his family and sending his children to school last year. So, they had to drop out. They would keep asking him when he would have enough money to send them to school. “I felt helpless and would cry quite often. I don’t want them to have a life like mine. I want them to study well. That’s what led to our education programme Vardhana. We put the farmer project on hold and decided to help those children who were on the verge of dropping out of schools due to financial constraints.

We spent a month in Latur interacting with families residing in drought-hit villages. There were several cases of farmer suicides reported in the region. We met one such family in Bise Wagholi. He was a pygmy agent who owned two acres of land in the village. Due to drought, they were unable to farm or grow anything in the past few years. Their second daughter Mohini was a bright girl. She had secured 80% in twelfth grade. They couldn’t afford to send her to college. So, they decided to get her married. One night, as they were discussing the demands of the other family, Mohini overheard them talking about dowry. Every proposal was declined due to their incapability of shelling out money. This particular family demanded Rs. 200,000. They spoke about selling the farm and taking a loan. Whatever, they would earn later could be given to the son, they told themselves.

The next morning, the mother went to the neighbor’s house to borrow some flour. They didn’t have anything to cook at home. When she returned, she saw Mohini’s lifeless body hanging from the ceiling. The little girl had committed suicide and she left them a note with questions. “Papa, why does a girl’s father have to pay dowry?” It read. She spoke of a society where girls would be able to fulfill their dreams. “Don’t waste any money on my funeral. Use it instead to give my brother and sister a decent education.” We read the letter over and over again for the next few days. It never felt that a little girl wrote it. She begged her father to stop drinking.

That was the last time he drank alcohol. Her mother sheds tears every time we passed by Mohini’s school. Today, they speak of the perils of dowry, and try their best to work hard and fulfill Mohini’s wishes of ensuring that son and daughter go to college and earn a degree.

“If we don’t demand dowry, people assume that something must be wrong with the boy. Why else would their family let go?” said the father to us, one morning. Like most families, they haven’t given up. And, they never will. They made a promise to their little girl to keep the hope alive and fight till their last breath.

In Thingdol, we spent a lot of time with a middle-aged farmer called Khuma. He lost one of his fingers in an accident when he was very young. He was trying to save himself from a swarm of bees and fell from a tree. He is a musician. He plays every instrument except the drums. “I never cried when my father died. I didn’t cry when my mother left me. But when I lost my finger, I wept for days. I can’t play like the way I used to,” he said. He would play the blues some nights on his guitar. He loved playing the violin. He learnt playing most of the instruments by listening to a few Myanmar stations on the radio. A year later, Akshatha gave her violin to Khuma. He got so emotional, and the following day he offered to give us a hen. For a tribal person, poultry and pigs are their source of wealth. We told him it wasn’t necessary and he didn’t have to give us anything. A few days later, he gave us some sticky rice. He said that God wouldn’t forgive him if he didn’t give us something. One of our friends who works with prosthetics in the USA has 3D printed a finger for Khuma. We had sent him the specifications a few months ago. It has arrived and we can’t wait to surprise Khuma the next time we go to Thingdol.

How can one volunteer, contribute to the causes you support?

People can reach out to us through our website and our facebook page to apply for volunteering or to contribute. All our projects are open for crowdfunding. (www.restofmyfamily.org). People can also donate via the Facebook page (Rest Of My Family)

Liked reading this? Then you might also like to read Nisha Gupta – International Level Para Athlete Who Campaigns For Inclusion Through Her Medals

If there’s any story that needs to be told, we will tell it. Write to us at contact@knowyourstar.com with your story lead, or contact us on Facebook or Twitter.